One of the greatest ironies of history consisted in a question that Pontius Pilate, the Roman procurator, asked of Jesus of Nazareth. Exasperated by Jesus’ enigmatic responses, Pilate finally expressed the question “What is truth?”

One of the greatest ironies of history consisted in a question that Pontius Pilate, the Roman procurator, asked of Jesus of Nazareth. Exasperated by Jesus’ enigmatic responses, Pilate finally expressed the question “What is truth?”

The irony consists in the fact that Pilate was looking into the eyes of Truth personified at that very moment. Christ, Himself, had told His disciples the previous night, “I am the way, the truth, and the life…” (John 14:6).

But was Pilate’s question so unreasonable? In it do we not find a legitimate search for a meaningful answer? After all, in a culture where there were as many gods as there were men to worship them, would it not be difficult for the average Roman to define in concrete terms what truth actually was and who it was that possessed it? I believe that the spirit of Pilate’s question lingers, especially in our day when the very nature of truth itself has been brought into question.

If the Foundations Are Destroyed…

Psalm 11:3 asks this question, “If the foundations are destroyed, what can the righteous do?” The modern Christian apologist faces a unique problem. In past times, the object of apologetic argumentation was to bring to light the truth and to dismiss the false, but in modern times the very notion of truth itself has been discredited, so that now the apologist must not only present the truth, but define what truth is. If the foundational understanding of truth is undermined, what can the righteous do?

We have all heard statements like this before.

“That may be true for you, but it is not true for me.”

“There is no such thing as absolute truth.”

“All truth is relative.”

“You cannot know the truth.”

“Truth depends on how you were raised.”

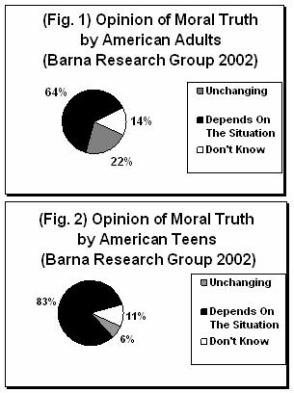

These statements may seem ridiculous or nonsensical, but they represent an increasingly prevalent trend of philosophy in the modern world (See figures 1 and 2). A trend, which if left unchecked, will render meaningful conversations about God and salvation nearly impossible.

So is truth an absolute and immutable fact, or is it relative to your perspective and culture? That is the question that the Christian apologist must be able to answer in order to lay a stable foundation for further proofs of his faith.

Truth Defined

Truth is that which corresponds with reality. Or to put it in the words of C. S. Lewis, “Truth is always about something, but reality is that about which truth is.”[i] This is known as the Correspondence Theory of truth, and is the only logically correct answer to the question of what truth is. All attempts to define truth in any other way are ultimately logically self-defeating.

Aristotle’s Definition of Truth

The Correspondence Theory of truth was first postulated by Plato’s famous student, Aristotle. In his Metaphysics, Aristotle states:

Now, in the first place, this is evident to those who define what truth and falsehood are. For indeed, the assertion that entity does not exist, and that nonentity does, is a falsehood, but that entity exists, and that nonentity does not exist, is truth. [ii]

To put Aristotle’s definition simply: truth is telling it like it is.

This may seem obvious or commonsensical, but Aristotle, by amplifying the teaching of Plato, was one of the first individuals to point out that truth is objective and not subjective. That is, truth exists outside of ourselves and does not conform itself to our opinions of it. For example, no matter how much I opine that the law of gravity does not exist, if I jump off of a tall building I will still fall. Once again, Aristotle states…

Statements and beliefs…themselves remain completely unchangeable in every way; it is because the actual thing changes that the contrary comes to belong to them.[iii]

Aristotle was basically saying that reality causes a statement to be true or false. Truth does not change reality, it agrees with it.

G. E. Moore’s Definition of Truth

G. E. Moore (1873-1958) was a philosopher and close personal friend of the famous agnostic, Bertrand Russell. He and Russell, despite their errors, are renowned for shedding light upon the Correspondence theory. Moore gives a definition of truth that closely resembles Aristotle’s, and helps to clarify the Correspondence Theory.

In Some Main Problems of Philosophy, Moore states, “To say that this belief is true is to say that there is in the Universe a fact to which it corresponds; and that to say that it is false is to say that there is not in the Universe any fact to which it corresponds.”[iv] In essence, Moore was saying that true beliefs correspond to facts (i.e. true ideas correspond to reality). He goes on to say, “When the belief is true, it certainly does correspond to a fact; and when it corresponds to a fact it certainly is true…and when it does not correspond to any fact, then certainly it is false.”[v]

In Moore’s postulation of the Correspondence Theory we understand a belief does not create fact to make itself true, but rather, a belief is true because it agrees with a fact that exists within reality.

The Liar Paradox

The Correspondence Theory has been the reigning theory of truth in Western thought for over two thousand years. It has not been without enemies however; for it was not long after that Aristotle had asserted his theory that it was met with criticism. Eubulides (a philosopher of the fourth century B.C.) postulated what is known as the “liar’s paradox” in an attempt to confound the correspondence theory. Eubulides asked his audience to consider the statement, “I am lying”.

The paradox is self-evident. If you say that the statement is true; it is really false, but if you say that the statement is false; it is actually true. So it seems that we find here at least and apparent problem with the correspondence theory of truth.

The answer to this objection is that it is logically self-defeating. Saul Kripke points out that such a statement is not grounded in a external matter of fact. While Bertrand Russel observes that this statment creates what is known as a metalanguage in which talk about the primary language is impossible. To quote Russell, “The man who says, ‘I am telling a lie of order n‘, is telling a lie, but a lie of order n + 1.”[vi]

[i] Lewis, C.S., God in the Dock, (Eerdmans, [2002 reprint of 1970 copyright]), taken from “Myth Became Fact”, p. 66

[ii] Aristotle, Metaphysics 4.7 1011b25-30, (Prometheus Books, 1991), translation by John H. McMahon

[iii] Aristotle, Categories 5.4a, From The Complete Works of Aristotle (Princeton University, 1984)

[iv] Moore, G. E., Some Main Problems of Philosophy, (Macmillan, 1953), p. 277

[v] Ibid. p. 279

[vi] Gardner, M., The Sixth Book of Mathematical Games from Scientific American, (University of Chicago Press, 1984), p. 222

April 4, 2008 at 6:42 pm

So then truth is not dependent on whether one believes it or not, but belief is dependent on the truth it is anchored in(reality or “what is”)?

If postmodernism is all about tearing down and deconstructing accepted views on truth and such, where can we begin to show bedrock foundations of truth where we can reconstruct truth for them?

April 5, 2008 at 12:02 pm

One thing that the Christian apologist can do is show the absurdities that arise from denying the basic logical principles that undergird the correspondence theory of truth. These absurdities not arise within the system of logical proofs, but also within real life as well. That is what I will be dealing with as I examine the principle of non-contradiction in part 2 of this subject.

April 7, 2008 at 8:39 am

[…] April 6, 2008 The Nature of Truth (Part 2): The Principle of Non-Contradiction Posted by Josh under Apologetics, Christian Thought, Christianity, Epistemology, Logic, Metaphysics, Philosophy, Problems of Philosophy, Truth (Click to see Part 1) […]

May 9, 2008 at 8:49 am

“When the belief is true, it certainly does correspond to a fact; and when it corresponds to a fact it certainly is true…and when it does not correspond to any fact, then certainly it is false.”

Based on the above, one could say that since there is no evidence that God exists, God must therefore not exist.

This also supports the idea that you can’t prove something isn’t; you can only prove something is.

In other words, you can’t prove God doesn’t exist; you can only prove God does exist. This has never been proven, so one must logically conclude that there is no God since there is no evidence of a God. Afterall, everything we think we know about God has been told to us by man, not by God.

May 9, 2008 at 2:34 pm

Hi Eran, thanks for stopping by.

I’m not sure that I follow your objection to Moore’s statement. It seems that you might be confusing metaphysics (fact: as in what actually exists) with epistemology (evidence: what warrants our belief in what exists).

Also, given the correspondence theory of truth, it is completely logically possible that a proposition could be true (correspond to some actual state of affairs), yet the person who believes it have no evidence that it is true; that is, their is a fact that corresponds to the statement, but not a known fact. Whether this person actually possesses knowledge or not is an epistemological question.

As to not being able to prove that something does not exist, that’s just not true at all. Given the correspondence theory of truth, I believe that I can ‘prove’ that 5 sided squares do not exist by merely explaing the terms as they correspond to reality. And I think that it would be possible to prove that God doesn’t exist if one were to find a clear logical contradiction in the primary attributes ascribed to God.

And as to their being no evidence for God: there are a lot of brilliant Christian scholars who would disagree with that assertion. Indeed, I think that there is evidence available to both sides in the debate concerning theism and atheism. One is convinced of the truth of their particular position when they affirm that the evidence in favor of it outweighs the evidence contrary to it. I happen to think that this is the case concerning theism.

Thanks again for the comment Eran, and stop by anytime.

October 26, 2008 at 10:07 am

Занимаюсь дизайном и хочу попросить автора quadri.wordpress.com отправить шаьлончик на мой мыил) Готов заплатить…

February 6, 2009 at 11:44 am

Hello Josh,

Your 5 sided square argument is not valid. You are trying to redifine a known condition. A square has 4 sides. Does a 5 sided object exist? Yes, it’s a pentagon. You have confused the issue by saying you can prove there is no 5 sided square. This question is an invalid argument.

Let me give you an example. I believe that invisible chocolate chip cookies float in space around us at all times and they rule the universe. These cookies are actually what we know as God. How would you prove they don’t exist? You can’t. You could only prove they do exist by somehow observing one. In my example, I’m not playing with word definitions.

Also, there are several clear logical contradictions in the primary attributes ascribed to God. God is alleged to be “all powerful.” If that is so, can God create a being more powerful than himself? If so, God is not all powerful. If not, God is not all powerful. Therefore, (1) God does not exist, or (2) God has limitations not ascribed to him.

Another example is that allegedly God is “all knowing.” If God knows all, why did he have to test Abraham to see if his faith was strong. God should have already known the answer.

“God is perfect.” Then, why did he create the flood to wash away his mistakes and start over?

Since there is absolutly no evidence that God exists, and there is absolutly no evidence that a God is required to exist, the highest probably is that there is no God.

February 6, 2009 at 10:57 pm

Hi Eran,

I’m having a difficult time following your line of reasoning here. In philosophical logic, an argument is valid if and only if the conclusion is true, then the premises must be true (or the conclusion follows from the premises). I did not give an argument proving the four sided square, I was simply stating that one can do so as an example that it is possible to prove that something is not: namely, that there cannot be a five sided square.

Thus:

Premise: Necessarily for every X, If X is a polygon, has four sides, and has four interior right angles, then X is a square.

Conclusion: Therefore a five sided square is not possible.

This is a valid argument.

Also, your argument concerning God’s omnipotence is a variation of the “stone paradox” which misdefines Divine omnipotence. If omnipotence means that a being with such an attribute can do the logically impossible, then the attribute is indeed incoherent. Yet theists have almost universally disavowed this definition of omnipotence. Thus, an omnipotent being is one that is capable of doing anything that can be done. An omniptent being cannot do the logically impossible: God CANNOT cease to exist, do evil, create a stone so large that he cannot lift it, or create a more powerful being (since he is the maximally powerful being).

Your other two examples depend on scriptural texts. However, these are not arguments against the existence of God, but the veracity of scripture. Such arguments boil down to scriptural hermeneutics (and there are many Biblical scholars who persuasively argue that these texts from scripture – when properly interpreted – do not violate the attributes of God). Besides, mistakes in the scriptural texts do not disprove the existence of God, only the fallability of said texts.

While I cannot prove that “invisible cookies that float in space” do not exist, I can know that they did not create the space-time universe, since the aforesaid “cookies” are material objects that exist in space. A spatio-temporal, material object could not have created the present universe since matter and space did not exist before the universe. Furthermore, a linguistic analysis of the proposition is incoherent (think about what ‘cookies’ are).

Once again, I question your declaration that there is no evidence for the existence of God. Many atheists philosophers will happily admit that there is indeed evidence for the existence of God (they just think that the evidence for the contrary is greater). The sames holds true for your statement that there is no evidence that a God is required to exist (many physicists and cosmologists believe in God precisely because they think that the existence of God is required for the existence of the universe).

As to empirical “observation” being the basis for all evidence, this is plainly mistaken. Can you observe the number 7? Or love or justice? Indeed, such a criterion for evidence is self-refuting. The statement “empirical observation is the basis of all knowledge” cannot be verified by empirical observation.

June 1, 2011 at 9:04 am

Exasperated by Jesus’ enigmatic responses, Pilate finally expressed the question “What is truth?”

June 1, 2011 at 9:06 am

Your 5 sided square argument is not valid. You are trying to redifine a known condition. A square has 4 sides. Does a 5 sided object exist? Yes, it’s a pentagon. You have confused the issue by saying you can prove there is no 5 sided square. This question is an invalid argument……

November 29, 2011 at 9:24 am

You say that: “…the Correspondence Theory of truth, is the only logically correct answer to the question of what truth is.”

In fact the Correspondence Theory of Truth is fatally flawed and is a completely discredited theory. Christians should not hang their hats on it. Truth is Not the property of Sentences. Please see my website.

March 21, 2012 at 12:03 am

email lists uk…

[…]The Nature of Truth (Part 1): What is Truth? « Quadrivium[…]…

May 21, 2012 at 9:57 pm

Foto Foto Lucu…

[…]The Nature of Truth (Part 1): What is Truth? « Quadrivium[…]…

July 28, 2013 at 9:10 am

You could certainly see your skills in the article

you write. The sector hopes for more passionate writers like

you who are not afraid to mention how they believe.

Always follow your heart.

July 28, 2013 at 4:15 pm

Have you ever thought about adding a little bit more than just your articles?

I mean, what you say is important and everything.

However think about if you added some great images or video clips to give

your posts more, “pop”! Your content is excellent but with images

and clips, this blog could definitely be one of the best in its niche.

Fantastic blog!

July 31, 2013 at 4:06 am

Hello are using WordPress for your site platform? I’m new to the blog world but I’m

trying to get started and set up my own.

Do you require any coding expertise to make your own blog?

Any help would be really appreciated!