By “moral dilemma” I mean a situation in which an agent ought to do A, ought to do B and cannot do both A and B. Experience seems to validate the existence of such dilemmas, and a plethora of illustrations have been offered as far back as Plato’s question of whether or not to return a promised cache of arms to a man intent on violence[1], to the heart-wrenching decision face by Sophie in Sophie’s Choice[2]. Such apparent dilemmas carry strong intuitive and emotional weight, and it does appear that, in certain circumstances, one is irrevocably caught in the horns of a dilemma which will lead to a failure of duty. However, I shall argue here that those who support the view that an adequate moral theory must allow for moral dilemmas do so at the cost of rejecting other important principles of adequacy for moral theories.

There are a number of principles by which a moral theory may be evaluated. Some of these principles may be regarded as necessary conditions for a moral theory, while others are meta-prescriptive in nature: detailing what a moral theory ought to require of agents[3]. Still others may be regarded as “good-making features” for a moral theory. In this paper I shall employ the following five principles:

- P1: A moral theory must be consistent.

- P2: A moral theory must be action guiding (decision-making procedure).

- P3: Requirements of a moral theory must be within the power of the agent to perform (“ought” implies “can”).

- P4: A moral theory must imply that it is morally desirable that agents should seek to avoid moral conflicts.

- P5: A moral theory must make sense of moral emotions.

I have listed the principles in order of their respective importance. (P1) and (P2) may be regarded as necessary conditions of any moral theory. Indeed, it seems impossible to even conceive of a moral theory which is inconsistent or fails to be action guiding. While there are a few who deny the truth of (P3), I shall argue below that (P3) can be understood as an extension of (P2). (P4) is meta-prescriptive in nature, while (P5) may be regarded as a good-making feature of moral theories.

(P1). Consistency

The most common charge leveled against those who support moral dilemmas is that of inconsistency. It is argued that the existence of genuine moral dilemmas leads to an incoherence that, in the words of W. D. Ross, “would be to put an end to all ethical judgment.”[4] This inconsistency, however, is not as apparent as it initially seems. Indeed, in order to demonstrate the inconsistency of moral dilemmas, one must first adopt certain principles of deontic logic.

In her essay, “Moral Dilemmas and Consistency”, Ruth Barcan Marcus demonstrates that the existence of moral dilemmas, in themselves, does not lead to a logical contradiction. Marcus points out that consistency is “a property that such a set has if it is possible for all of the members of the set to be true, in the sense that contradiction would not be a logical consequence of supposing that each member of the set is true.”[5] Thus moral dilemmas do not necessarily imply inconsistency because it is possible for moral dilemmas to arise contingently yet each principle of the underlying moral theory to be true.

Marcus uses a “silly two-person card game”[6] to illustrate this point. In this game, black cards trump red cards and high cards trump cards of lower value. A potential dilemma is cited as occurring when a red ace is turned up against a black deuce. Initially, this does seem to lead one to conclude that the rules of the game are inconsistent. However, Marcus points out that such a conclusion is mistaken since it is possible for all the rules to be obeyed in some worlds and for a conflict to never arise. The rules are contingently inconsistent but not necessarily so. According to Marcus, opponents of moral dilemmas are making the same mistake as the opponents of the card game: they do not recognize that it is possible for moral dilemmas to arise within a moral theory whose underlying principles are all true.

Thus, while opponents of moral dilemmas seek to deny the very possibility of dilemmas, the charge of inconsistency cannot be used insofar as it applies to the truth of ethical principles in themselves. In order to make the charge of inconsistency stick, one must tie the ethical principles to logical principles so that a moral dilemma can be stated as a logical contradiction (an agent is required to do A and ~ A).

There are two axioms of deontic logic which are commonly appealed to by opponents of moral dilemmas. These two principles, when employed together, yield a logical contradiction in moral dilemmas:

- D1. OA → ~O ~A

- – If it ought to be that A then it ought to be that not A (it is permissible that A).

- D2. * (A → B) → (OA & OB)

- – If it ought to be that A implies B, and if A is obligatory, then B is obligatory.

Using these two principles, the argument demonstrating the inconsistency of moral dilemmas can be stated thus:

| (1) |

OA |

| (2) |

OB |

| (3) |

~¯(A & B) |

| |

(Premises 1, 2, and 3 constitute the standard definition of a moral dilemma.) |

| (4) |

OA → ~O ~A (principle D1) |

| (5) |

* (A → B) → (OA → OB) (principle D2) |

| (6) |

O ~(B & A) (from 3) |

| (7) |

O (B → ~A) (from 6) |

| (8) |

O (B → ~A) → (OB → O ~A) (from 5) |

| (9) |

OB → O ~A (from 7 and 8) |

| (10) |

O ~A (from 2 and 9) |

| (11) |

OA and O ~A (from 1 and 10) |

| (12) |

~O ~A (from 1 and 4) |

| |

|

Thus, using the two axioms of deontic logic above leads to a logical contradiction of (10) and (12).

Any attempt to reject the above argument requires one to deny either (D1) or (D2), or both (D1) and (D2). While (D1) is so basic that there is little controversy regarding its validity, there have been a few concerns with (D2) (such as Ross’s paradox and forms of the Good Samaritan paradox). Nonetheless, (D2) still seems to be quite basic and the burden of disqualifying these principles rests firmly upon the shoulders of the supporters of moral dilemmas.

(P2). Action Guiding

Another condition of adequacy for any moral theory is that it provides an agent with moral guidance (even if indirectly). Indeed, one can hardly conceive of a moral theory that does not provide instruction for what one ought to do. However, many consider (P2) to be too weak, thus leading to the following revision:

P2I: A moral theory must be uniquely action guiding.

That is, a theory should not fail to offer guidance in a moral situation nor should it recommend incompatible actions to an agent. Since one of the primary purposes of a moral theory is to give direction to agents, it seems only fitting that a moral theory be uniquely action guiding. Theories that allow for dilemmas, however, do suggest incompatible actions to agents and thus are not uniquely action guiding.

Supporters of moral dilemmas will often point to symmetric cases in which the agent is required to choose between two perfectly equal options. Take, for example, a mother who has twin daughters suffering from leukemia. The mother can undergo a bone marrow transplant for only one of the girls, thus the daughter who receives the transplant will live and the other daughter will die. Supporters of dilemmas argue that in such cases there can be no unique guidance for actions since the choices are equal.

Given the above example, however, opponents of dilemmas can point out that moral theories can still be uniquely action guiding since symmetrical situations like the one cited above present a disjunctive obligation. Since the best act that the mother can do in such a situation is to save one of her daughters, then that is her duty. Indeed, such a concept seems quite natural in other situations. If a dying wealthy uncle can only choose one of his noble nephews to bequeath his wealth, it hardly seems a moral failure if he does so. Thus the option of a disjunctive obligation to maintain a uniquely action guiding moral theory is available to those who reject moral dilemmas, while supporters of dilemmas are forced to accept theories that fail to be uniquely action guiding.

(P3). ‘Ought’ Implies ‘Can’

The principle of ‘ought’ implies ‘can’ is one of the most intuitive of moral theories. Many consider it to be a condition of adequacy for moral theories. Essentially, the theory asserts that the requirements of a moral theory must be within the power of the agent to perform; that is, if an agent ought to do an act he should be capable of doing so. However, those who support the view that an adequate moral theory must allow for moral dilemmas can find the principle to be quite problematic, since opponents of dilemmas have used the principle to argue for the inconsistency of such theories.

Opponents of dilemmas employ the principle of ‘ought’ implies ‘can’ as well as the agglomeration principle to construct an argument which demonstrates the inconsistency of moral dilemmas. These two principles are represented thus:

- D3. A OA → ¯A

- – For every A, if it ought to be that A, then it is possible that A.

- D4. (OA & OB) → O (A & B)

- – If it ought to be that A and it ought to be that B, then it ought to be that A and B.

With these two principles, the argument can be represented thus:

| (1) |

OA |

| (2) |

OB |

| (3) |

~¯(A & B) |

| |

(As above, premises 1, 2, and 3 constitute the standard definition of a moral dilemma.) |

| (4) |

A OA → ¯A (principle D3) |

| (5) |

(OA & OB) → O (A & B) (principle D4) |

| (6) |

(OA & OB) → ¯(A & B) (an instantiation of 4) |

| (7) |

OA & OB (from 1 and 2) |

| (8) |

O (A & B) (from 5 and 7) |

| (9) |

~O (A & B) (from 3 and 6) |

| |

|

And so, by employing (D3) and (D4), opponents of dilemmas can demonstrate a contradiction in (8) and (9).

Supporters of dilemmas have three options available to them in order to avoid the conclusion of the above argument: they can reject (D3), they can reject (D4), or they can reject both (D3) and (D4). An example of the third option can be found in the fourth chapter of Walter Sinnott-Armstrong’s Moral Dilemmas[7], and since (D4) is widely regarded to be a basic axiom of deontic logic, I will examine Sinnott-Armstrong’s rejection of (D3).

In rejection of (D3), Sinnott-Armstrong offers what he considers to be an example which demonstrates that there are some cases when a moral agent ought to perform an act but cannot.[8] In this example Sinnott-Armstrong asks the reader to suppose that Adams promises at noon to meet Brown at 6:00 p. m. However, Adams chooses to go to a film which starts at 5:00 p. m. Due to the distance which separates the move theater from the meeting place, Adams will be unable to meet Brown when he promised. Thus, if the principle (D2) holds, at 5:00 it cannot be true that Adams ought to meet Brown at 6:00, since Adams cannot do so.

Something does, indeed, seem strange about this account. Sinnott-Armstrong points to the fact that most people would agree that Adams still ought to meet Brown since he made the promise to do so earlier in the day. Since he cannot however, principle (D2) must be false.

However, there is something even more troubling about this example which Sinnott-Armstrong fails to point out. It would appear that principle (D2) grants any agent the option of being relieved from his obligations by simply taking actions to ensure that he cannot fulfill his duty. Yet this certainly does not seem right. The problem with the above example is that it fails to take into account the fact that when an Adams willfully placed himself in a situation in which he would be unable to fulfill his obligation he failed to perform his duty at that time. Therefore it is no longer the case at 5:00 that Adams ought to meet Brown, since Adams has already failed to keep his promise by choosing to go to the film.

One may still wonder what it is that makes principle (D3) map onto our intuitions so strongly. I believe that this is because (D3) extends from (D2). Remember that (D2) states a moral theory must be action guiding; that is, it must be able to give moral direction to agents. With that in mind, suppose that Jane gives her teenaged son, Ralph, a list of things that need to be done around the house. The list reads thus:

- 1. Wash the car and shampoo the carpet at the same time.

- 2. Mow the lawn and clean the shower at the same time.

- 3. Clean the oven and fold the laundry at the same.

One can only imagine poor Ralph’s consternation at reading such a list! Not only will it be impossible for Ralph to follow such directions, this list seems to lack any real direction at all (at least direction that is intended to be followed). Likewise, moral theories that deny principle (D3), fail – on at least some occasions – to be action guiding.

(P4). Avoiding Moral Conflicts

It seems intuitive that a moral theory should direct agents to avoid moral conflicts whenever possible. Yet some supporters of dilemmas, such as Ruth Marcus, argue that moral dilemmas must exist because there is a moral duty to act in such a way as to prevent moral conflicts:

The point to be made is that, although dilemmas are not settled without residue, the recognition of their reality has a dynamic force. It motivates us to arrange our lives and institutions with a view to avoiding such conflicts. It is the underpinning for a second-order regulative principle: that as rational agents with some control of our lives and institutions, we ought to conduct our lives and arrange our institutions so as to minimize moral conflicts.[9]

Marcus’ argument, which is a form of what has been referred to as the “moral residue argument”, can be stated in the following modus ponens form:

- If one ought to desire to not knowingly act in such a way as to bring about a moral conflict then moral conflicts are dilemmatic.

- One ought to desire to not knowingly act in such a way as to bring about a moral conflict.

- Therefore moral conflicts are dilemmatic.

The above argument is valid, so opponents of dilemmas must focus on the truth of the premises, and the second premise (a restatement of (P3)) seems plainly true. Indeed, Terrance McConnell, a noted opponent of moral dilemmas, acknowledges the truth of the second premise when he states, “One cannot plausibly deny that it is morally desirable for agents to minimize the conflicts they face.”[10] McConnell, as well as other foes of dilemmas, does take issue with the first premise and argues that there is an alternate explanation that accounts for the moral force of the second premise.

McConnell gives the example of making a promise to two individuals – Juan and Helga – that you will meet them at a given time. However, the time at which you promised to meet Juan and Helga is the same so that you cannot fulfill both promises. McConnell agrees with Marcus that making such a promise is wrong in that leads to inevitable moral conflict: either Juan or Helga are going to be frustrated because of your decision. The point at which McConnell disagrees with Marcus is whether or not you must engage in yet another wrongdoing because of the moral conflict in which you find yourself. Marcus, who would argue that the moral conflict in question is a moral dilemma, would say that another wrong is inevitable. McConnell, on the other hand, denies that another wrong must take place. Indeed, McConnell argues that the moral conflict in which one wrongly placed oneself is an entirely new situation which requires a new decision that is based upon which choice is morally superior. The moral ledger has been reset, as it were.

Initially, the position may seem to be incorrect. Indeed, the alarm bells of intuition begin to ring when one considers the inevitable frustration and disappointment that will be brought about by failing to keep your promise to one of your friends. McConnell acknowledges this intuition, but points out the friend’s disappointment and frustration are not the result of an additional wrongdoing, which stems from the neglected horn of a moral dilemma, but that her frustrations are the result of the original wrongdoing of placing oneself in a moral conflict. Furthermore, McConnell correctly points out that the friend’s future frustration cannot be what made the original decision of placing oneself in a moral conflict wrong, since your friend could very well die before the time of the promised rendezvous, but your earlier conflicting promises would still be wrong, since making such conflicting promises shows disrespect for the individuals to whom they are made. Thus the wrongness of placing oneself in a moral conflict, contrary to the second premise of Marcus’ argument, is not based upon a moral conflict presupposing a moral dilemma. Therefore Marcus’ argument is unsound.

Furthermore, McConnell points out that the duty to be careful to not place oneself in a moral conflict still holds even if the conflict in question is easily resolved. He uses the example of breaking a trivial promise to save an accident victim’s life: while nearly everyone would agree the aforementioned action is morally correct, if the agent in question had made the trivial promise with knowledge of the future conflict she would have been wrong in doing so due to the disrespect shown to the individual to whom the false promise was made. Since one commonly held aspect of moral dilemmas is that they are irresolvable, it is clear that the duty to be careful to avoid moral conflicts cannot be based upon the existence of moral dilemmas since it is wrong to knowingly place oneself in a moral conflict, even when the said conflict can be easily resolved.[11]

(P5). Making Sense of Moral Emotions

It is naturally desirable that a good moral theory be able to make sense of moral emotions, and many supporters of moral dilemmas actually consider (P5) to strengthen their case. This “phenomenological argument” in favor of moral dilemmas argues that since one feels guilt after making a difficult choice in a situation of moral conflict, then one must indeed be guilty. There have been various illustrations of the above argument, but the one thing that they all have in common is the insistence that perceived guilt (or remorse) indicates actual guilt.[12]

Opponents of dilemmas agree that remorse is only appropriate when an agent has actually done wrong. However, they are apt to point out that just because one experiences remorse does not mean that one has done something worthy of remorse. There are many cases in which an individual may experience incredible feelings of guilt, yet, according to outside observers, has done nothing wrong.

Consider the example of Matthew, an amateur golfer who is enjoying a game on a weekday afternoon. After a particularly wild swing, Matthew’s shot slices in the direction of a nearby street and strikes the windshield of a school bus filled with children. The distraction from the impact causes the driver to lose control and the bus runs off the road eventually rolling into a ditch. Many of the children are seriously injured, and a few are killed.

Of course, no one should legally or morally fault Matthew for the accident and the consequent deaths and injuries of the children, however few would find it unsurprising that Matthew, after discovering that it was his ball that caused the accident, should be filled with grief and experience feelings of guilt over what had taken place. Indeed, it would seem strange if Matthew did not experience such emotional pain, since we know how we would, ourselves, would feel in such a situation. Nevertheless, while Matthew’s grief and regret over the tragic accident may – and should – be considered appropriate, the same cannot be said for his feelings of remorse. Indeed, one could even say that Matthew’s experience of guilt is, although understandable, irrational.

Supporters of dilemma are not the only ones who appeal to (P5) in favor of their position. Opponents of dilemmas have their own phenomenological arguments against the existence of moral dilemmas. One of these arguments appeals to the practice of seeking moral advice in an apparent dilemma, another points out the phenomenon of moral doubt that often occurs after a decision has been made in an apparent dilemma.[13]

In situations of moral conflict, and especially when the alternatives appear to be symmetric, it is a common practice for an agent to seek moral counsel concerning which decision to make. However, if a moral conflict is genuinely dilemmatic, it would be irrational or dishonest to advise an individual to choose one alternative over the other. Indeed, the only sound advice in such cases would be to simply instruct the individual that they will fail in their duty no matter which choice they make. But this is not how we perceive the nature of seeking and giving advice to be. Thus, the opponent of dilemmas argues, if an agent feels the need to seek advice for a solution to her problem, and the advisor feels the need to give advice because there is a solution to the problem, this must be because moral conflicts are not genuinely dilemmatic.

The second phenomenological argument against dilemmas focuses on the doubt that an agent is apt to experience after making a difficult decision involving moral conflict. According to this argument, if one is in a genuine dilemma, there is no reason for doubting one’s decision after the fact since doubt implies that the agent is concerned over whether or not she made the right choice. In a genuine dilemma, there can be no right choice. Thus the existence of moral doubt disproves the reality of moral dilemmas.

Objections offered by supporters of dilemmas against the above two arguments are very similar in character to the objections given by the opponents of dilemmas. One may say that it is irrational for an agent to seek advice or have moral doubts in certain situations; however, the burden of proof rests upon the supporters of dilemmas as to how one may determine these situations. Furthermore, the arguments given above clearly demonstrate that the position of supporters of dilemmas is not significantly strengthened by (P5), and that opponents of dilemmas can construct similar arguments.

Conclusion

The debate concerning moral dilemmas will probably continue for a long time to come, and there are many other arguments and considerations to be examined about the matter. However, it seems apparent that those who argue that an adequate moral theory must allow for moral dilemmas find themselves in a troublesome situation in regards to other conditions of adequacy for moral theories. Until the supporters of moral dilemmas can account for these apparent weaknesses, it seems that only moral theories that exclude dilemmas should be considered adequate.

[1] Plato, The Republic, Book I, trans, G. M. A. Grube, in Plato: Complete Works, John M. Cooper and D. S. Hutchinson (eds.), Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Company.

[2] Styron, William, 1980, Sophie’s Choice, New York: Bantam Books

[3] See Terrance McConnell, “Metaethical Principles, Meta-Prescriptions, and Moral Theories”. American Philosophical Quarterly. Volume 22, Number 4, 1985.

[4] Ross, W. D., Foundations of Ethics, Oxford University Press, 1939, p. 60.

[5] Marcus, Ruth. “Moral Dilemmas and Consistency”. The Journal of Philosophy. 87.3 (1980): p. 129.

[6] Ibid., pp. 128-129.

[7] Sinnott-Armstrong, Walter, 1988, Moral Dilemmas, Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

[8] Ibid., pp. 116-121.

[9] Marcus, Ruth. “Moral Dilemmas and Consistency”. The Journal of Philosophy. 87.3 (1980): p. 121.

[10] See Terrance McConnell, “Moral Residue and Dilemmas”, Moral Dilemmas and Moral Theory. ed. H. E. Mason. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996. p. 44

[11] Marcus, incidentally, avoids this criticism by holding the position that all moral conflicts constitute moral dilemmas. One must question, however, if the benefits that Marcus’ theory gains from exempting itself from this objection outweigh the very unpalatable position that all moral conflicts lead to inevitable wrongdoing.

[13] See Terrance McConnell, “Moral Dilemmas and Consistency in Ethics”. Moral Dilemmas. ed. Christopher Gowans. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1987. pp. 163-169.

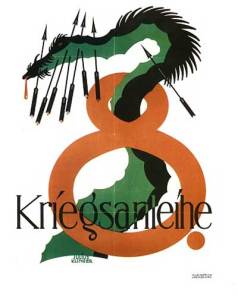

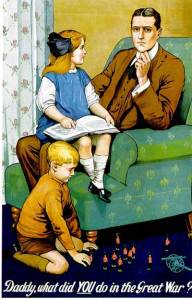

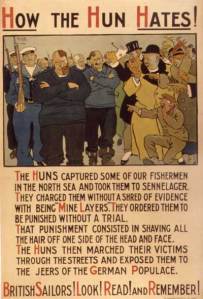

In the First World War humanity was horrified at the advent of trench warfare, u-boats, tanks, and casualties on an unprecedented scale as nations rapidly discovered new and more brutally effective ways to slaughter one another’s citizens. However, war-fueled innovation extended beyond the bomb-blasted battlefields of the Eastern and Western fronts; it began in the home front, as the concept and practice of war propaganda flourished.

In the First World War humanity was horrified at the advent of trench warfare, u-boats, tanks, and casualties on an unprecedented scale as nations rapidly discovered new and more brutally effective ways to slaughter one another’s citizens. However, war-fueled innovation extended beyond the bomb-blasted battlefields of the Eastern and Western fronts; it began in the home front, as the concept and practice of war propaganda flourished.